Key Iterations: Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments

Translated by Claude from the Chinese original.

This article is a summary with excerpts from Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments (the Chinese edition is titled “Key Iterations”). More specifically, these are notes from an Airbnb reader on a technical book whose authors and translators are also from Airbnb. Please point out any errors; comments are welcome.

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. —Abraham Maslow

Preparing for Tests

To Succeed, Fail More

The cognitive shift brought by experiments is also related to the gap between expectations and reality.

If you think something will happen and it does, you won’t learn much. If you think something will happen but it doesn’t, you’ll learn something important. If you originally thought something was insignificant but it produced surprising or breakthrough results, you’ll learn something extremely valuable.

Teams develop a product feature because they believe it’s useful. However, in many domains, most ideas fail to improve key metrics. At Microsoft, only one-third of tested ideas improved target metrics. In already highly optimized product areas like Bing and Google, success is even harder—test success rates are only 10%-20%. Bing’s team of hundreds of ranking algorithm engineers has an annual goal of improving a single OEC metric by 2%.

Testing Is Tactical, Decision-Making Is Strategic

When testing bold ideas, the way experiments are run and evaluated also changes.

- Experiment duration: A small temperature increase won’t cause change in a room, but once the melting point is reached, ice begins to melt.

- Number of ideas tested: Each experiment tests only one specific tactic—a component of the overall strategy. Individual experiment failures don’t mean the overall strategy is flawed. But if many tactics evaluated through controlled experiments fail, it’s likely a strategy problem. Using experiments to validate strategy is extremely costly; strategy should primarily be informed by existing data.

One interpretation of OKR is: define the strategic O (Objective), then derive a series of tactics from the KRs (Key Results) to achieve those KRs and ultimately feed back into O.

What Are Significant Results?

Not all statistically significant results have practical meaning. Take revenue per user as an example: how large a difference is important from a business perspective? In other words, what level of change is practically significant? Building this substantive boundary is important—it helps understand whether a difference is worth the cost of the corresponding change. If your website, like Google and Bing, has billions of dollars in revenue, a 0.2% change is practically significant. By comparison, a startup might consider even 2% growth too small, as they’re pursuing 10% or greater improvements.

In 2012, every 10-millisecond performance improvement at Bing (1/30th of a blink) was enough to justify the cost of hiring a full-time engineer for a year. By 2015, that number had dropped to 4 milliseconds.

Setting Up Tests

Variant Assignment

How to assign experiments to users:

- Single-layer method: Bucket users—say into 1,000 buckets—and use two user buckets per experiment.

- Parallel experiments:

- Divide the code architecture into layers, with only one experiment per layer.

- Don’t worry about experiments interfering with each other; assume all experiments are orthogonal. If non-orthogonal experiments exist, rely on the execution team to discover and resolve conflicts.

Metric Classification

- Goal metrics, also called success metrics or North Star metrics, reflect what the organization ultimately cares about. Being able to clearly articulate your goal in words is important, because the translation from goal to metric is usually imperfect. Your goal metric may only be an approximation of what you truly care about and needs iterative improvement over time. Helping people understand this limitation—and the distinction between the metric and the goal statement—is crucial for keeping the company on the right track.

- Driver metrics, also called signpost metrics, proxy metrics, indirect metrics, or predictive metrics, are generally shorter-term than goal metrics, changing faster and more sensitively. Driver metrics reflect a mental causal model—a hypothesis about how to make the organization more successful, i.e., assumptions about the drivers of success, rather than what success itself looks like.

- Guardrail metrics ensure we make the right trade-offs on the path to success and don’t violate important constraints.

Metric Selection

Metric selection, beyond statistical validity, also depends on the designer’s value choices (“people are ends, not means”). Metrics represent how you want the system to understand data and what you care about. For example, use P95/P99 to focus on extreme values, or mean and median for overall trends.

Proxy Metrics

Some subscription services renew on an annual basis. Unless you’re willing to run a year-long experiment, it’s hard to measure the impact on renewal rates. In such cases, we can’t use renewal rate as the experiment metric and instead need to find proxy metrics, such as service usage, which can indicate user satisfaction early and ultimately influence renewal rates.

Metric Normalization

Even if you want to increase total revenue, it’s not recommended to use total revenue as the metric, since it depends on the number of users in each variant. Even with equal allocation, actual user counts may differ due to randomness. We recommend normalizing key metrics by actual sample size—hence revenue per user is a good overall evaluation criterion.

Duality

Sometimes it’s simpler to precisely measure what you don’t want rather than what you do want—such as user dissatisfaction or unhappiness. Establishing causal relationships from observational data is difficult, but a carefully conducted observational study can help disprove false hypotheses.

Preventing Sub-Metric Conflicts

Carefully examine each sub-metric under a major metric—sub-metrics may conflict with each other. For example, search engine queries per user = sessions per user × unique queries per session.

A session starts when a user begins their first query and ends when the user has no activity on the search engine for 30 minutes.

- Sessions per user is most likely a positive metric—the more users like the search engine, the more frequently they use it, increasing sessions per user.

- Unique queries per session should decrease, which conflicts with the overall goal. A decrease in unique queries per session means users need fewer steps to solve their problem—but it could also mean users are abandoning their queries. We should ideally pair this metric with a query abandonment metric.

Pitfalls

Beware of Extreme Results

When we see surprisingly positive results (e.g., major improvements to key metrics), we tend to construct a narrative around them, share, and celebrate. When results are surprisingly negative, we tend to find some limitation or minor flaw in the study and dismiss it. Experience tells us that many extreme results are more likely caused by instrumentation (e.g., logging) errors, data loss (or duplication), or calculation errors.

Simpson’s Paradox

Two groups of data that satisfy a certain property when examined separately may lead to the opposite conclusion when combined.

When an experimental feature causes individuals to migrate between two mutually exclusive and exhaustive segments, similar situations can occur (though the book emphasizes this isn’t Simpson’s paradox per se).

For example, a feature that moves Level 2 users back to Level 1 might improve both levels’ data—Level 2’s user pool removes poorly performing users while Level 1’s pool gains better-performing users—but overall performance across both levels may stay the same or even worsen.

Ideally, segmentation should only use values determined before the experiment, so the experiment doesn’t cause users to change segments. In practice, however, this is hard to enforce in some cases.

Changing User Base

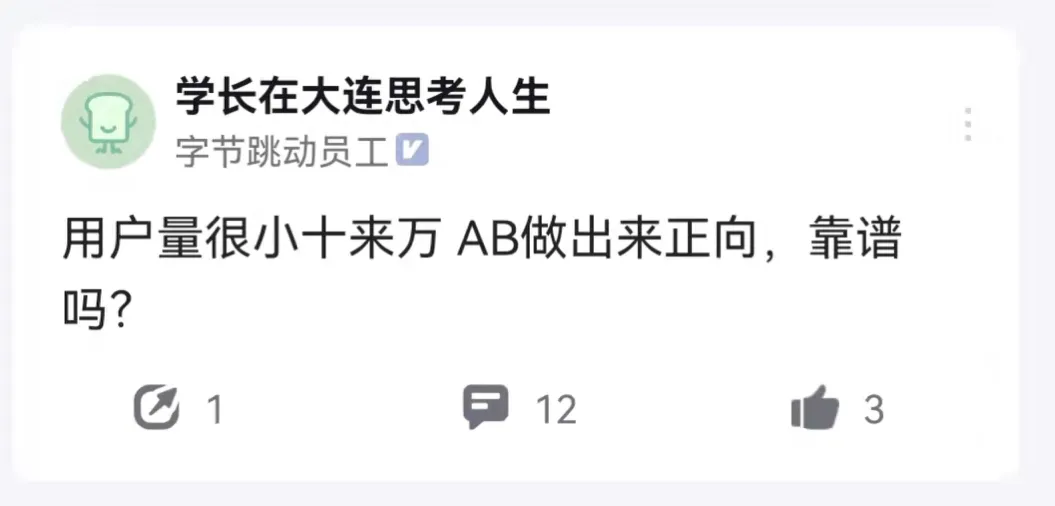

When computing metrics or running experiments, all data comes from the existing user base. Especially for early-stage products and startups, early users may not represent the user base the business hopes to acquire for long-term growth.

Uncertain Confounding Factors

Shared resources and dependencies can cause experiments to fail:

- Market resources: Homestays and ride-sharing have this problem—once supply becomes constrained, one group capturing too many resources deprives the other group of its original resources.

- Advertising campaign budgets.

- Model training for recommendation systems: Once both models are trained on full user data, knowledge sharing between the two models is likely within days.

- CPU or other computational resources.

Others

Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

The Lucas Critique observes that relationships found in historical observational data cannot be considered structural or causal. Policy decisions change the structure of economic models, so historical correlations no longer hold. Over time, even the causal relationships we previously relied on may change.

Long-Running Experiments

Reasons why short-term and long-term experiment results may differ:

- User learning effects.

- Network effects.

- Delayed experience and evaluation.

- Ecosystem changes:

- Launching other new features.

- Seasonality.

- Competitive landscape.

- Government policies.

- Concept drift.

- Software performance degradation.

Methods for improving long-running experiments:

- Cohort analysis: Long-term tracking of a stable cohort’s user data.

- Post-period analysis: After running for a period, close the experiment (or roll it out to all users), then continue measuring the difference between control and treatment groups.

- Time-staggered experiments: Use experiment start time t as a variable to create multiple treatment groups, comparing user performance differences across different values of t.

- Holdback and reversal experiments:

- Holdback: Keep 10% of users in the control group.

- Reverse: After several months, move those 10% back into the control group. Then measure user performance.

Ethics

- Respect for persons: Respect experiment participants as autonomous individuals and protect them when they lack this capacity. This principle focuses on transparency, truthfulness, and voluntariness (choice and consent).

- Beneficence: Protect people from harm. Properly assess risks and benefits, and appropriately balance them when reviewing proposed research.

- Justice: Ensure participants are not exploited and that risks and benefits are fairly distributed.

An Example: Designing a Slowdown Experiment

Why can a slowdown experiment measure the impact of speed improvement on a product?

Assume that the relationship between a relevant metric (e.g., revenue) and performance (e.g., speed) can be well approximated by a linear fit near the current value. This is essentially a first-order Taylor expansion, or linear approximation.

That is, if we improve performance, the resulting metric change can be approximated by the metric change obtained from degrading performance.

Two additional reasons support this assumption:

- From our own experience as users, faster is always better for website speed.

- We can also verify the linearity assumption—for example, test the metrics at 100ms delay and 250ms delay, and check whether the metrics at these two points follow a linear relationship.

Alternative Methods

How do we measure counterfactuals? Consider an experiment with a human population as test subjects. To determine the deviation between counterfactual and reality:

Outcome of affected group - Outcome of unaffected group

= (Outcome of affected group - Outcome of affected group had they not been affected) +

(Outcome of affected group had they not been affected - Outcome of unaffected group)

= Effect of the change on the affected group + Selection bias

What we can observe is the performance of affected vs. unaffected groups, but what we want to know is the effect of the change on the affected group. So we want the selection bias in the system to be zero.

A/B testing is a system with zero selection bias, but in many real situations we can’t apply A/B testing to real problems—for example, there’s no randomization unit, the experiment would waste significant (opportunity) costs, or the experiment would be unethical.

These methods generally serve as alternatives to A/B testing, but they usually have larger estimation error and bias:

- Interrupted time series: Split the experiment time into many small segments, uniformly (and randomly, or just round-robin) assign each segment to different treatments, then measure and analyze (some time-series models can be useful, such as Bayesian structural time series analysis).

- Interleaved experiments: Often used for ranking algorithms—show Algorithm A at odd positions and Algorithm B at even positions to compare differences.

- Regression discontinuity design: Consider this method when the affected population is identified by a clear threshold. Use the group just below the threshold as the control and the group just above as the treatment, comparing these two groups to reduce selection bias. For example, studying the impact of scholarships on students where students scoring 80+ receive scholarships—we study the 80-84 and 75-79 score groups.

- Instrumental variables and natural experiments: If we can find an instrument within the studied process that helps achieve random grouping, we can use it for causal analysis. For example, draft lotteries for military conscription or school assignment—if the lottery process is random, it can serve as the randomization unit.

- Propensity score matching: Although we can’t randomize, if we can identify confounding factors (covariates) between groups that might affect our judgment of the variable, or if we can determine that unidentifiable confounding factors won’t affect analysis, then we can analyze causal relationships between variables and outcomes. This is usually very difficult to achieve.

- Difference-in-differences: Identify a control group as similar as possible to the treatment group, assuming both groups share the same trends. For example, select two cities with similar characteristics as control cities—enable the new feature in one but not the other, then compare differences between the two cities.

These types of analyses should be used carefully, as they may fail due to:

- Common causes: Smaller palms correlate with longer lifespans—actually, women live longer.

- Spurious or deceptive correlations: The length of words in the National Spelling Bee positively correlates with the number of people killed by venomous spiders that year—but this is obviously spurious.

Mathematical Derivation

We use a two-sample t-test to calculate the p-value, which matches the actual experimental setup.

Where

Considering the variance formula for independent variables

Where

The p-value is essentially a conditional probability: “the probability of observing the current difference or an even larger one, given that the null hypothesis is true,” i.e.,

Some people mistakenly interpret the p-value as “the probability that the null hypothesis is true, given that we observed the current or larger difference.” The implicit condition “observing the current or larger difference” has a probability specific to each experiment and lacks universality. The relationship can be derived using Bayes’ theorem:

Variance-Related Issues

P-value calculation depends on variance. Common issues with variance estimation:

Variance Calculation for Percentage Deltas and Ratio Metrics

Note that if the metric’s meaning and the analysis unit differ, values may not be independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.). For example, calculating page conversion rate while the experimental unit is the user—users visiting a page multiple times makes page-level data non-i.i.d. In this case, variance needs to be calculated from the numerator and denominator of the ratio formula separately, not by first computing the ratio and then calculating variance.

The correct calculation: we express the ratio metric as the ratio of two user-level metric averages:

Via the delta method (skipping the derivation), the final variance formula is:

Outliers

Outliers can interfere with experiments. A reasonable threshold can be added to observed metrics; other methods can be researched independently.

Improving Sensitivity

Lower variance means higher significance. These methods can reduce variance:

- Transform metrics through thresholding, binarization, and log transformation: Purchase amounts have larger variance than whether a purchase was made; per-user watch time has larger variance than whether viewing exceeded x hours.

- Remove noise through trigger analysis.

- Stratify within the sampling scope through stratified sampling, control variables, or CUPED. Combine results from each stratum to get the total—variance calculated this way is smaller.

- Choose finer-grained randomization units.

- Shared control group: Calculate an appropriately sized control group and compare it against multiple treatment groups. This reduces variance and can improve statistical power for all treatment groups, though it introduces some issues.

P-Value Threshold Issues

Beware of this fact: when the significance threshold is 0.05, testing a no-op feature (where the null hypothesis is true) 100 times means that, statistically, about 5 tests will incorrectly conclude significance (false positives). Here we introduce two concepts:

- Type I error: The measurement shows a significant difference, but in reality there is no difference.

- Type II error: The measurement shows no significant difference, but in reality there is a difference.

A smaller significance threshold (

To reduce the aforementioned “5 out of 100 tests incorrectly concluding significance” Type I errors, we can apply a stricter significance threshold to metrics confirmed to be unrelated (or indirectly related) to the experiment. The more confidence we need, the lower the significance threshold should be.

Conversely, for sensitive guardrail metrics where missing a real change is costly, we may use a less strict significance threshold together with explicit power targets. Especially for metrics where we explicitly require that fluctuations not exceed x%, we should follow the industry principle that tests should have 80% statistical power (statistical power = 1 - Type II error rate; see specific approximation formulas elsewhere), and calculate thresholds based on x.

How Large Should Sample Size n Be?

This section overlaps somewhat with the sensitivity improvement section.

What’s the theoretical basis for “larger n is better”? In practice, many t-test settings rely on the sample mean being approximately normal. According to the Central Limit Theorem, under appropriate conditions, the mean of a large number of mutually independent random variables converges in distribution to a normal distribution after proper standardization. So n needs to be sufficiently large.

The statistical power approximation formulas mentioned earlier can help calculate n given certain conditions, but these formulas require specifying the effect size x%. This is only suitable for some guardrail metrics.

To better approximate normality of the mean, we can also use empirical formulas based on skewness to calculate n. Metrics with large variation often also have high skewness. We can reduce skewness and n by capping differences (e.g., treating all values above 10 as 10), as long as capping doesn’t violate our assumptions.

We can also verify by constructing a null distribution, but the concepts involved are more complex, so we’ll skip that here.

TBD: Why Choose the t-Distribution?

This requires comparing the characteristics of several sampling distributions—refer to the summaries in university textbooks.