Notes on A Philosophy of Software Design

Translated by Claude from the Chinese original.

About six months ago, I borrowed A Philosophy of Software Design from a friend who had not finished it yet, and then left it unread myself. During the National Day holiday, I spent three on-and-off days finishing it. The most useful part for me was its revised-edition pushback against some views in Clean Code. Software engineering is still a young discipline: there are best practices that many people agree on, but almost nothing is universally correct. I had also seen many of this book’s ideas in other books, sometimes in a stronger form. For example, this book explains why inheritance can be problematic but spends less time on alternatives, while Effective Java explicitly argues to “prefer composition over inheritance,” and The Pragmatic Programmer also discusses extensibility.

The book’s discussions on complexity are very helpful for software development, while the other parts are more ordinary—experienced developers can skim them quickly.

Definition of Complexity

Summarized by a formula: software complexity is the sum of each component’s complexity multiplied by how frequently it’s modified. That is, to reduce software complexity, we can either lower individual component complexity or take a holistic view and place highly complex logic in modules that are modified less frequently.

Growing complexity brings 3 problems:

- Increased modification complexity—one change requires changes everywhere.

- Heavier cognitive burden—needing to understand too many concepts before knowing how to make changes.

- Unknown unknowns—not knowing what knowledge is needed to understand a problem, let alone how to acquire it. Even if the engineer makes incorrect changes or misses some changes, they have no way of knowing.

Tangled dependencies between code lead to problems 1 and 2, while missing critical information (e.g., inconsistencies between code and documentation) leads to problems 3 and 2.

Strategic Programming vs Tactical Programming

- Strategic programming: Prioritizes overall software design. Minimum viability and shortest time are not considered in isolation (though reasonable development costs and working code are important parts of design).

- Tactical programming: Using the shortest programming time to produce minimally viable code.

Note that “strategic” here still operates within agile cycles, not the waterfall model. In waterfall, projects are too large with execution times and feedback cycles too long, which is unfavorable for designing better software architecture.

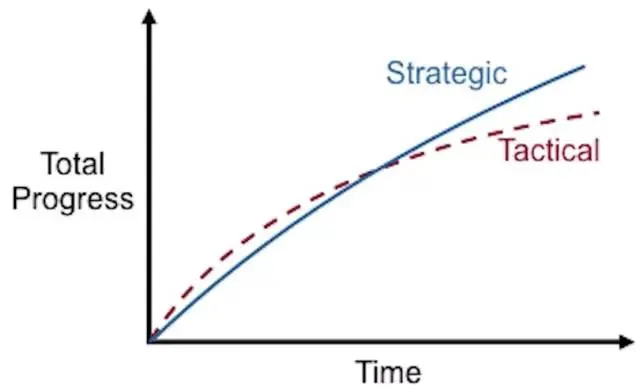

The book says that investing 10%-20% more time beyond tactical programming can transform it into strategic programming. I disagree—strategic programming generates a lot of throwaway work from various comparisons and research. Overall, I believe rigorous strategic programming costs about twice as much as bare-minimum tactical programming. However, I very much agree with one illustration in the book: with strategic programming, progress and time spent have a nearly linear relationship, while with tactical programming, achieving one unit of progress requires nearly exponential development time investment. This is because strategic programming leverages good architecture to hide complexity, making each unit of progress as independent as possible from existing code. Tactical programming, on the other hand, often means every piece of new code must account for existing old code, making the burden increasingly heavy.

The 10-20% time mentioned in the book reminds me of:

- Google’s 20% free work time.

- Asana dedicates one week per quarter specifically to software refactoring. (Accounting for vacation and the fact that engineers don’t spend all their time coding, this is also close to 10%?) I read about this in The Effective Engineer—I helped review the Chinese edition, so go buy it!

The book argues that good code attracts better developers, and that some startups believe tactical programming lets them move faster and they can hire better developers to fix the code later once the business takes off—but this approach is inadvisable. I think this is certainly true for a technology company, but for a business-driven company, it may depend on whether the business itself actually needs strong technical support. Some businesses genuinely don’t.

Modules Should Be Deep

A module is “deep” when it hides substantial implementation complexity behind a small and convenient interface.

The book gives a fascinating example: GC in Go and Java. The implementation is very complex, but GC means the language does not need to expose manual memory-management interfaces to users. Even when we add substantial internal complexity, good modularization can still reduce the number of exposed interfaces.

The GC example feels similar to the server-compute/client-render pattern: centralizing complex computation in one place means clients do not each need to maintain their own copy of that logic.

The author also notes that some modern developers tend to make functions and classes smaller and smaller, which can also make them shallow (not deep). This is worth keeping in mind during everyday development.

Information Hiding (and Leaking)

This chapter argues that different modules should own orthogonal (unrelated) concerns. I summarized the traits emphasized by the examples:

- Low coupling

- After breaking a large function into multiple smaller ones, those smaller functions should not depend on each other. Pay special attention to call order: whether a function executes correctly should not depend on specific preceding functions having run.

- It’s unreasonable for both a file-read module and a file-write module to carry file-format parsing knowledge. Consider merging them into one read-write module, or extracting file-format parsing into a separate module.

- High cohesion

- Code generating an HTTP response should not first set the HTTP version and then delegate the response to other modules. Instead, responsibility for setting protocol details should be encapsulated in the relevant modules.

- Hide implementation

- A class that internally uses a map should not expose that map directly. Otherwise external code can mutate internal state, and replacing the map with another implementation later becomes much harder.

The More General, the Simpler

(My loose translation—the original heading is “General-Purpose Modules are Deeper.” In this book, “deep” refers to modules that hide significant complexity behind a simple interface.)

My understanding is: once complexity is reduced to a certain point, it is often transferred rather than eliminated. Distributing complexity between interface and implementation determines how often users encounter that complexity. Usually, the simpler and more general the interface, the more complex the implementation, and thus the deeper the module.

The author also emphasizes that designing general interfaces does not mean over-designing. A general interface may accommodate future needs, but those needs may never arrive, or may even break the existing interface. So we can preserve interface generality while implementing only current requirements. If new needs emerge later, we can extend internals behind the same interface and make the module deeper.

Different Layers, Different Abstractions

Different layers should have different abstractions. If different layers share the same abstraction, it often indicates that the code at those layers isn’t deep enough.

For example, the classic Principle of Least Knowledge: in a call chain A -> B -> C, if B only forwards requests to C, then A should call C directly instead of B. Adding code always increases complexity, so we must evaluate whether new code brings enough benefit. In this case, B adds complexity without benefit and increases future maintenance costs.

The book also discusses decorators and pass-through variables.

Regarding decorators, Java and Python provide relatively ergonomic language support. In other languages, the author suggests considering alternatives to decorators:

- Add the new functionality directly into the decorated method or object.

- If the decorator adds functionality for special cases while the decorated method handles general cases, consider whether these special cases can be handled elsewhere.

- Add the new functionality into other existing decorators.

Pass-through variables are values that must be threaded through every method in a call chain, such as Go’s ctx context.Context. The author suggests using something like thread-local storage to keep context in an instance, but I don’t think there is a universally good solution today. A potentially cleaner approach might be thread-scoped dependency injection (for example, via frameworks like Guice): delegate thread-local read/write mechanics to the framework, let it inject available values automatically, and expose only remaining values to callers. I have not used this approach in production yet.

In Defense of Long Functions

The book mentions Robert Martin’s Clean Code, which advocates that functions should be as short as possible.

However, the author disagrees that all functions should be as short as possible: “Each method should do one thing and do it completely.” If a function is hard to decompose into shorter independent units, or if the extracted functions still depend on shared context, that kind of decomposition can increase complexity and maintenance cost.

Comments

Should We Write Comments?

Here the author again explicitly disagrees with Clean Code, which treats comments as a “necessary evil” and argues that comments often indicate failure to write expressive code.

The author argues that comments and code are complementary: together they reduce complexity, and missing comments can increase it. For example, comments can reduce the need for excessively long function names (the book’s example: isLeastRelevantMultipleOfNextLargerPrimeFactor) and can avoid forced decomposition into many short but interdependent functions.

Function comments let callers use code without reading implementations, which is itself a form of abstraction. Comments can also capture design information that cannot be fully expressed in code alone.

Comments Should Describe Non-Obvious Parts of Code

The author discourages writing information in comments that can be directly derived from reading the code. The book’s counterexample:

ptr_copy=get_copy(obj) #Get pointer copy

if is_unlocked(ptr_copy): #Is obj free?

return obj #return current obj

Comments can be classified into these categories, each with different standards:

- Lower-level comments: Help developers understand certain details in the code more precisely.

- Higher-level comments: Help developers intuitively understand what the code does without reading it.

- Interface documentation: Doesn’t describe implementation details, but lets developers know how to use the corresponding interface. Good interface documentation represents good abstraction; if interface documentation must describe internal implementation, the underlying implementation may be too shallow.

- Implementation comments: Describe what the code does and why, but don’t need to describe how—because the code itself contains that information (what and why, not how).

For cross-module designs shared by multiple modules, the author suggests writing notes in shared structural definitions, or adding a designNotes file to the source code.

Write Comments First, Code Second

The author believes writing comments after finishing code isn’t a good habit, because writing comments after all code is done increases the resistance to writing them. Also, after finishing code, some critical information may have already been discarded by the brain and is difficult to recover.

This is similar to how I write reading notes immediately after finishing a book—it’s the most efficient approach.

So the author advocates writing comments first, then code.

A common counterargument is that code usually goes through several rounds of changes before it stabilizes, so writing comments only at the end seems more efficient. But the author argues that repeatedly modifying code is more expensive than iterating on comments first. Writing comments in advance helps stabilize structure; if the design keeps changing, revise the comments first, where iteration is cheaper.