Thoughts on the Video Quality Evaluation

Last year, I led the team behind OpusClip’s LLM-as-a-Judge system. Since we already published a post about video quality evaluation, I can share a short recap here. I am currently working on a separate evaluation track for AgentOpus, so I will close with a related question that I find personally interesting.

What We Did Last Year

You can check the blog for full details; below is a short summary.

Our goal was to build a video quality judge system that can score video quality across different rubrics.

Building the First Rubric

The first step was data collection. We collected 300 samples from both internal and external sources. With a target agreement rate of 80% and a 95% confidence level (±5% margin of error), the minimum required sample size is about 246. [1]

At the same time, we defined rubrics for the judge. We set up a number of rubrics under the hook, content, visual, and audio categories. The first rubric we annotated manually was hook engagement. I asked everyone on the team, as well as external experts, to annotate videos. It was important that human annotators achieve an 80% agreement rate first.

The annotation result for each video is simple: Does the video meet the rubric? The result is 0 (does not meet), 1 (partially meets), or 2 (meets). As the annotation progressed, we needed to rebalance the dataset to ensure the number of 0/1/2 samples remained roughly equal.

Once we had the annotation results, we tested different prompts on Gemini 2.5 Pro (and later Gemini 3 Pro). The prompt that aligned most with human annotations was selected as the “judge” for the current rubric.

Scaling to More Rubrics

Once we knew how to build the judge for one rubric, scaling to others was straightforward. We sped up the annotation process via LLM pre-annotation, reducing the number of annotators needed for high-agreement samples. We also built an internal agent to iterate on prompts across different rubrics automatically.

In the end, we had an LLM-as-a-Judge system that gave quality scores for videos. A video’s quality score equals the sum of its per-rubric results (each 0, 1, or 2), yielding a score range of 0 to 2N for N rubrics.

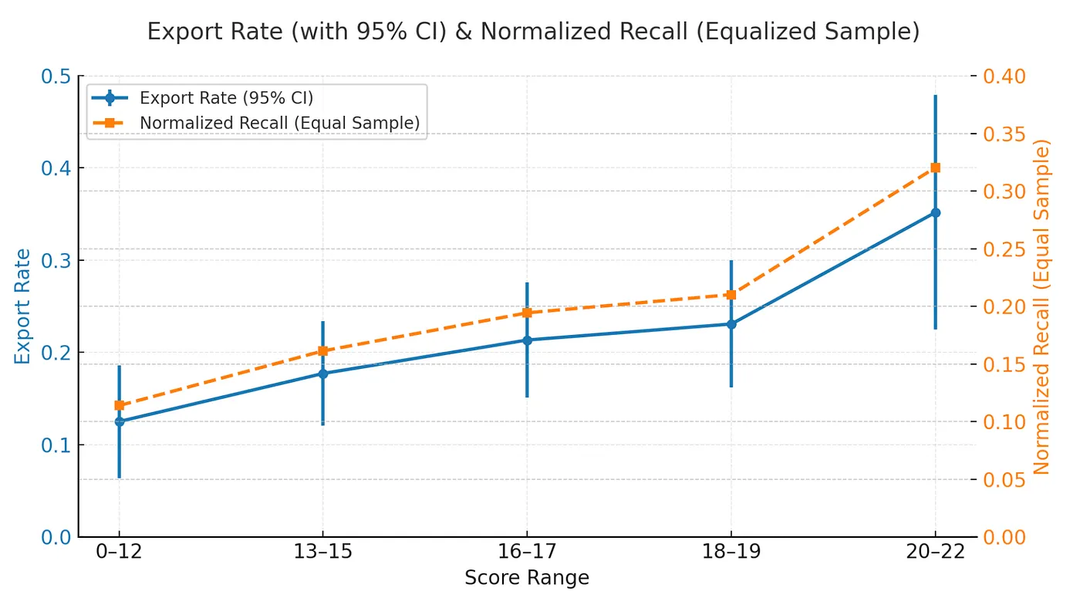

We also cross-validated the judge by testing it on new samples and calculating the correlation between export rate and judge score. The results show that a higher judge score indicates a higher export rate.

Figure 1. Judge score vs. export rate on a holdout set. Each point represents a score bucket. The trend is monotonic: higher judge scores are associated with higher export rates.

Results

We used this system to curate clipping strategies produced by another system, and it improved our online export rate. The system also worked effectively on our B2B customer clips, increasing business metrics for other teams.

These results gave me confidence in rubric-based quality judging. At the same time, they raised a question I find personally interesting: can an evaluation infer a plausible execution path from the final result? I am still exploring this direction, but it seems promising for making agent evaluation more interpretable.

What Am I Curious About This Year?

The core question is: can an evaluation do more than assign a score — can it also explain why the agent failed?

This matters for two reasons:

- If the agent is too weak (in other words, useless), the evaluation becomes meaningless because we may not have an effective way to use it to improve the agent itself.

- On the other hand, if we can infer an execution path from a result, then we can transfer that knowledge into the agent. As a result, the agent will have the same knowledge as the evaluator.

OpenAI has a very interesting approach: they ask Codex CLI to evaluate its own performance. What I learned from this is that we should try to put the evaluator and the agent at the same level, so that when the evaluator improves the agent, the agent can also improve the evaluator.

With that, we can build a data flywheel — a self-improving bootstrap for the agent. Then we can iterate on its performance quickly by feeding more data and more cases into the system.

I am still early in exploring this direction, but the underlying question feels worth asking: if your evaluator could hand the agent a concrete diagnosis instead of just a score, how would that change the way you build and iterate on agent systems?

n = z² · p · (1 − p) / e², with z = 1.96, p = 0.8, e = 0.05. This assumes approximately independent samples and uses raw agreement as the primary metric. ↩︎